In order to learn from history, one has to know about it first. Even then, it is hard to do – arguably, human nature is constant, but how it manifests is ever changing, as the circumstances change, mostly due to innovation, which has led some to observe that history rhymes more so than it repeats, which is also hard to assess, as there is only one human history, in other words observing counterfactuals is impossible – there is neither a control group, nor the possibility of experiments. All of which makes “lessons from history” far more ambiguous than one would like.

But I rather seriously digress, and in the very first paragraph, no less. Back to the question, which could be phrased as “How aware are we of things that happened before we were born?, “How well will things that are popular today be remembered in the future?”, “How fleeting is fame and what determines which ideas will stand the test of time?”

Anecdotally, the answer to the first questions is “not very”. Every year, Beloit College publishes an updated “Mindset List” that attempts to highlight all the things that students who are now entering college are completely unaware of, as they have never used a typewriter, floppy disks, don’t know about VHS or cassette tapes, and so on. While amusing, such considerations raise deeper scientific questions: How well do cultural artifacts age in the collective memory? Will future generations have any awareness of things that are popular today?

Of course, there is longstanding interest in the question of what is in the cultural awareness, as exemplified by wild but popular speculations about archetypes, but scientific answers have been wanting until relatively recently.

One such investigation pertains to American presidents and Chinese leaders, both picked because the list of entries is comprehensive and known. In brief, the results show that collective memory mirrors individual memory – there are strong primacy and recency effects. In terms of American presidents, this manifests as knowing the first few and the most recent view, but most people would be hard pressed to name an American president from the middle of the 19th century other than Lincoln.

This paints a rather depressing picture of cultural transmission. As time progresses, most events will be “somewhere in the middle”, so are we doomed to live the cultural version of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, with relatively little transmission between generations?

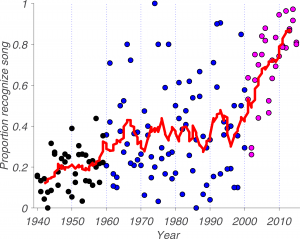

A somewhat more positive picture emerges when considering cultural artifacts that people seek out, e.g. music. Looking at onetime number 1 hits, we could show that recognition of these songs does not hit zero about a decade before our participants were born – what one would get if one extrapolated the steep drop-off implied by the recency effect.

Instead, recognition hits a rather stable “plateau” of moderate recognition that extends for 3 decades. Averaging is somewhat misleading, as there is tremendous inter-song variability in this period. Some are as well recognized as if they were released yesterday, whereas others are completely forgotten.

What drives this difference seems to be exposure, as measured by Spotify playcounts. In other words, we can’t tell whether music from the 60s to 90s was truly special, or whether recognition rates for things people seek out (music) are higher than for things people don’t (political leaders) in general.

The good news is that cultural transmission seems to work better than previously thought, at least for things that people are seeking out. Whether music is a fluke or not in this regard could be investigated by looking at other things like popular movies or books.