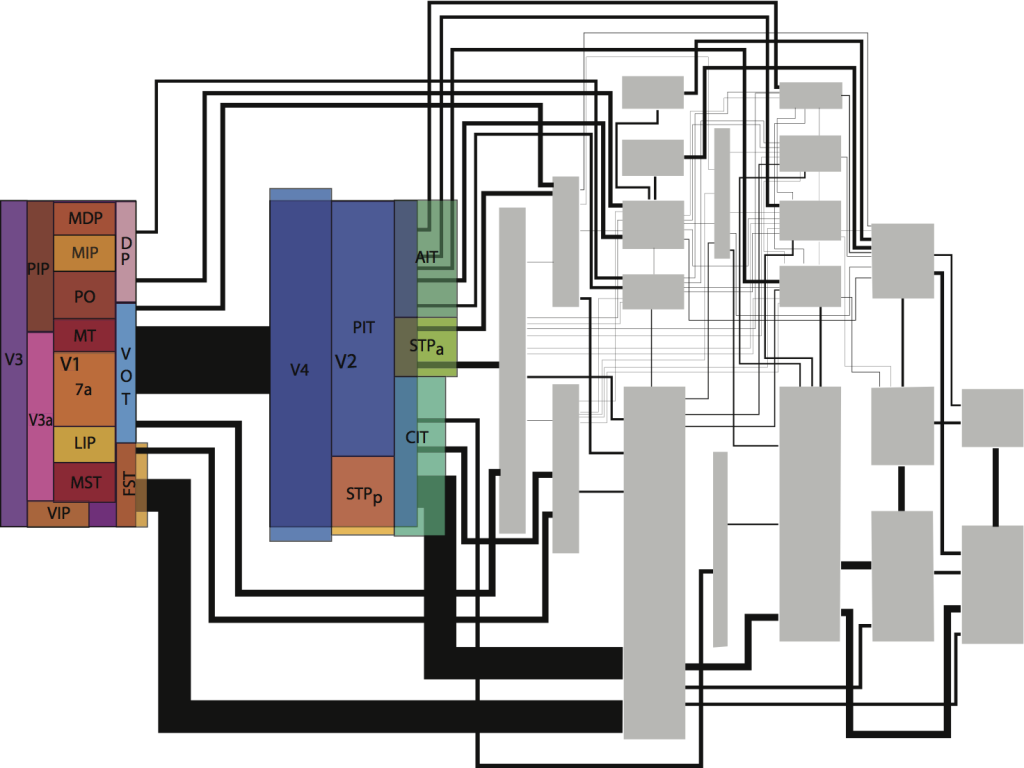

The visual system of primates comprises a large number of distinct cortical areas containing neurons that modulate their activity in response to a visual stimulus and are believed to represent different aspects of the visual scene. It has been recognized since the 1980s that these areas are roughly organized as “early” visual areas (primary visual cortex or V1 and V2) followed by two parallel (dorsal and ventral) but hierarchical visual streams. What is usually underappreciated is how much cortical real estate is taken up by the early visual system, i.e. V1 and V2. This matters, as the biggest bottleneck in the entire system is on the level of V2 outputs (at least within cortex). The scene is likely to be represented at a fine grain in the early visual system, but not afterwards. Put differently, what happens before V2 (mostly) stays in V2. To illustrate this point, we took a page out from a popular infographic meme and superimpose the rest of the visual system onto V1 and V2. To do so, we modified a figure from Wallisch et al. (2008), see figure 1. In this figure, size of the area is scaled proportional to its cortical surface area.

Figure 1. The higher visual system, superimposed on V1 and V2. As you can see, individual areas of the higher visual system are on the scale of small European principalities while V1 and V2 most resemble land empires in Asia or America. Modified with permission from Wallisch et al., 2008.

As you can see, V1 easily accommodates the entire dorsal stream (and then some) and V2 almost fits into the ventral stream (although not quite, because V4 is so big). Neatly, this is consistent with earlier reports regarding the design limitations of the visual system.