Technological change often entails social change. Historically, many of these changes were unintended and could not be foreseen at the time of making the technological advances. For instance, the printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1400s. One can make the argument that this advance led to the reformation within a little more than 50 years and the devastating 30-years war within another 100 years of that. Arguably, the 30-years war was an attempt at the violent resolution of fundamental disagreements – about how to interpret the word of god (the bible), which had suddenly become available for the masses to read. Of course the printing press was probably not sufficient to bring these developments about, but one can make a convincing argument that it was necessary. Millions of people died and the political landscape of central Europe was never quite the same.

Which brings us to social media. I think it is safe to say that most of us were surprised how fundamentally we disagree with each other as to how to interpret current events. Previously, the tacit assumption was that we all kind of agree about what is going on. This is obviously no longer possible and often quite awkward. Social media got started in earnest about 10 years ago, with the launch of Twitter and the Facebook News Feed. Since then, people have shared innumerable items on social media and from personal experience, one can be quite surprised how different other people interpret the very same event.

Which brings us to my research.

Briefly, people can fundamentally disagree about the merits of any given movie or piece of music, even though they saw the same film or listened to the same clip.

Moreover, they can vehemently disagree about the color of a whole wardrobe of things: Dresses, jackets, flipflops and sneakers. Importantly, nothing anyone can say would change anyone else’s mind in case of disagreement and these disagreements are not due to being malicious, ignorant or color-blind.

So where do they come from? When ascertaining the color of any given object, the brain needs to take illumination into account, a phenomenon known as color-constancy. Insidiously, the brain is not telling us that this is happening, it simply makes the end-result of this process available to our conscious experience. The problem – and the disagreement – arises when different people make different assumptions about the illumination.

Why might they do that? Because people assume the kind of light that they usually see, and this will differ between people. For instance, people who get up and go to bed late will experience more artificial lighting than those who get up and go to bed early. It stands to reason that people assume to happen in the future what they have experienced in the past. Someone who has seen lots of horses but not a single unicorn might misperceive a unicorn as a horse, should they finally encounter one. This is what seems to be happening more generally: People who go to bed late do assume lighting to be artificial, compared to those who go to bed early.

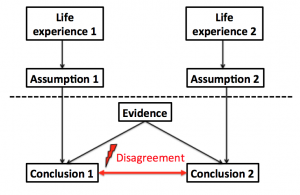

In other words, prior experience does shape our assumptions, which shapes our conclusions (see diagram).

Conclusions can be anything that the brain makes available to our conscious experience – percepts, decisions, interpretation. Objects above dashed line are often not consciously considered when evaluating the conclusions. Some of them might not be consciously accessible. Note that this is not the only possible difference between individuals. Arguably, it might be that the brains are also different from the very beginning. That is probably true, but we know next to nothing about that. Note that differing assumptions are sufficient to bring about differences in conclusions in this framework. That doesn’t mean other factors couldn’t matter as well. Also note that we consider two individuals here. Once more than two are involved, the situation would be more complicated yet.

If this is true more generally, three fundamental conclusions are important to keep in mind, if one wants to manage disagreement positively:

1. There is no point in arguing about the outcomes – the conclusions. Nothing that can be said can be expected to change anyone’s mind. Nor is it about the evidence (what actually happened), as the interpretation of that is colored by the assumptions.

2. In order to find common ground, one would be well advised to consider – and question – the assumptions you and others make. Ideally, it would be good to trace someone’s life experience, which is almost certain to differ between people. Of course, this is almost impossible to do. Someone’s life experience is theirs and theirs alone. No one can know what it is like to be someone else. But pondering – and discussing – on this level is probably the way to go. Maybe trying to create common experiences would be a way to transcend the disagreement.

3. As life experiences are radically idiosyncratic, fundamental and radical disagreements should be expected, frequently. The question is how this disagreement is managed. If it is not managed well, history suggests that bad things might be in store for us.