Imagine you are looking at a screen – much like you are doing now. On this screen are moving dots and you count how often they collide with each other. While you are doing that – unbeknownst to you – an unexpected moving square is entering the screen from the right and moves until it exits on the left side of the screen. Would you be surprised to learn that the *less* time the square is visible on the screen, the *more* likely you would be to notice it? Most people would – understandably – find that quite surprising. And yet, that is what is happening. As this might sound a bit counterintuitive, we have to go on a bit of a detour to fully understand it. So please bear with us, we promise it is all relevant.

For the first two years of WW2, the US Navy did not possess a functional torpedo. This sounds like an incredible claim, given that the war in the Pacific made especially strong use of such weapons. The reason for this is that the Empire of Japan relied heavily on long supply lines throughout the Pacific rim (as the Japanese home islands are resource poor) rendering them particularly vulnerable to submarine attack. In theory, the US Navy possessed a very advanced weapons system – the Mark 14 torpedo – to get the job done. This torpedo featured several key innovations, one of them being that instead of detonating when colliding with the – often armored – side of the target ship, like conventional torpedoes (which usually requires multiple hits to sink a ship) it would run underneath it, when the steel of the ship would trigger the magnetic proximity fuse of the torpedo, setting off an explosion from directly underneath that would break the back of the ship and sink it with a single torpedo.

So far the theory. And yet, between December 1941 and November 1943, over ⅔ of Mark 14 torpedoes fired in anger failed to detonate, most of them running harmlessly beneath the Japanese ships. How is this possible and what does this have to do with cognitive psychology?

The principal reason for the failure of Mark 14 torpedoes to detonate consists in the fact that they were running too deep, which did not trigger the magnetic proximity fuse as the torpedo was in fact much too far, and not proximate to the hull. The Mark 14 torpedo had a depth control mechanism that was designed to maintain a set depth below the surface which relied on a calibrated hydrostatic gyroscope system. This system was also state of the art for the time. So what was the problem and how could it persist for so long?

The crux of the problem is that when the torpedo is moving, cavitation creates turbulence, lowering the water pressure at the sensor locally, which will make the hydrostatic system that controls its depth believe that it is running too shallow, which will make the torpedo dive deeper in order to adjust. So far the key problem. The reason why it was not discovered for so long was that at first – incredibly – only static torpedos were tested, as this made retrieval easier, and the static torpedoes could maintain any desired depth that was set by the operators. Only when submariners frustrated by far too many duds insisted on realistic live firing exercises were they finally performed. Once the problem was identified and fixed, the US silent service had a very effective weapon in the form of the Mark 14, using it to devastating effect in 1944 and 1945.

There were several other testing-related issues involving the Mark 14 as well, but the key take home message here is that it does matter a great deal under which conditions a system is tested, and whether these conditions are realistic or not. If they are not, even severe problems could remain undetected.

This issue is not restricted to torpedoes or war. If an alien civilization found a piston-engine aircraft in a hangar and only tested it inside of it, aircraft would be very puzzling contraptions, and their true purpose would not be immediately obvious. Proper context matters.

Psychology often suffers from a similar problem. Many times, phenomena that appear to be devastating biases and deficits – for instance the “baserate fallacy” – disappear when investigated under more ecologically valid conditions. For instance, it can be shown that if doctors are presented with information about the accuracy of medical tests in terms of the probabilities that the test results will be false positives or false negatives, they are systematically unable to do so. Specifically, they overestimate the probability that a patient with a positive test result actually has the condition, if the medical condition is rare. This has been interpreted as “baserate neglect”, the inability of most doctors to take the low baserate into account when making their calculations. This is puzzling, as the doctors are certainly smart enough to do so, but they empirically don’t.

However, it can also be shown that if the very same doctors are presented with the exact same information in terms of natural frequencies instead of probabilities, doctors can reason about this problem just fine and come up with the correct answer, without exhibiting baserate neglect. Apparently, these doctors are able to handle this information just fine, if they encounter it in the format that brains would have encountered it most of evolution: relative counts. In contrast, as the concept of probability is a relatively recent cultural invention that is only a few hundred years old, one would not expect brains to be particularly comfortable with probabilistic information.

To summarize – what can appear as a cognitive deficit or an impairment of reasoning – baserate neglect – disappears, when tested under conditions humans would have encountered for most of their evolutionary history.

This state of affairs seems to also be true for other cognitive domains, such as attention.

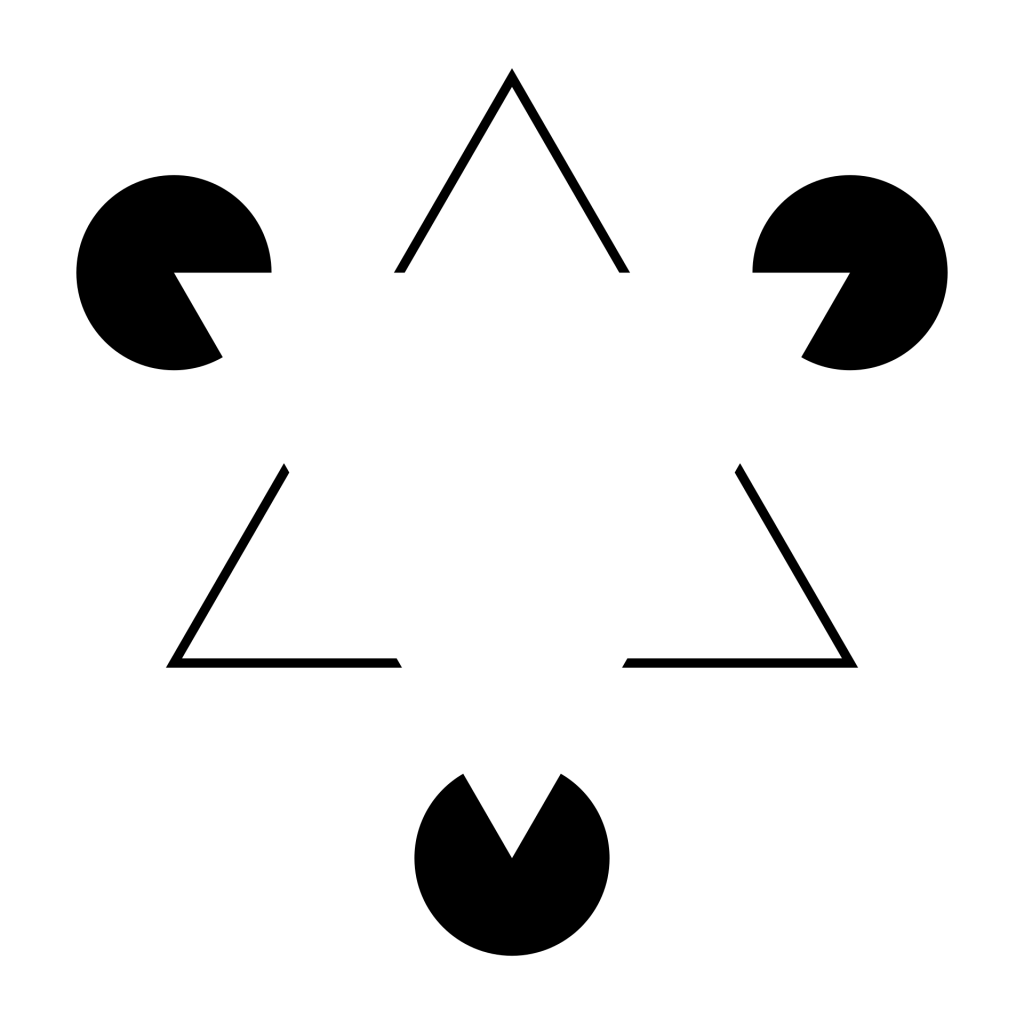

Inattentional blindness is the failure of an observer to notice unexpected but readily perceivable stimuli when they are focusing on some task. This phenomenon has been documented in many contexts, even including unexpected stimuli that are moving. It is commonly explained in terms of the overriding strength of top-down goals and expectations over bottom-up signals and often seen as an inescapable flip side of focusing attention. In other words, the benefit an observer gets from deploying attentional resources to task-relevant stimuli is paid in form of an increased likelihood of missing less relevant stimuli.

Importantly, this phenomenon is often interpreted as a deficit, as it manifests as a pervasive failure of observers to notice unexpected objects and events in more and less serious real world settings, from the failure of experts to notice a gorilla embedded in radiographs to the failure to notice Barack Obama to the failure to notice brawls while on a run, the latter which could have implications for the veracity of eyewitness accounts and on and on.

Some even went so far as to suggest that inattentional blindness might be an inescapable cognitive universal, insofar as it has been documented in every culture it has been tested.

Given how prevalent and – indeed inescapable and deleterious – the phenomenon of inattentional blindness seems to be, it struck us that it would leave organisms in an extremely vulnerable state.

As we are all the offspring of an unbroken chain of organisms who all successfully managed to meet the key evolutionary challenge of reproduction before disintegration, this seems implausible.

It could be argued that the real cognitive task all organisms are engaged in is the management of uncertainty. Specifically, an organism does not a priori know which stimulus type in the environment is most relevant. Of course, there are some potential stimuli that are either expected or consistent with goals, but that does not mean that unexpectedly appearing threats might not suddenly be more relevant. Thus, it would be unwise if an organism overcommitted to focusing attention solely on those it deemed relevant at the time it decided to focus. In other words, there should be a path for evolutionarily relevant stimuli to override top-down attention.

Fast motion is an ideal such stimulus, for several reasons. First, most organisms devote a tremendous amount of cortical real estate to the processing of visual motion. Second, motion is generally a fairly good life-form detector. Third, fast objects are particularly likely to be associated with threats like (close) predators. Fourth, fast moving stimuli are relatively rare in the environment, which makes false positives less likely.

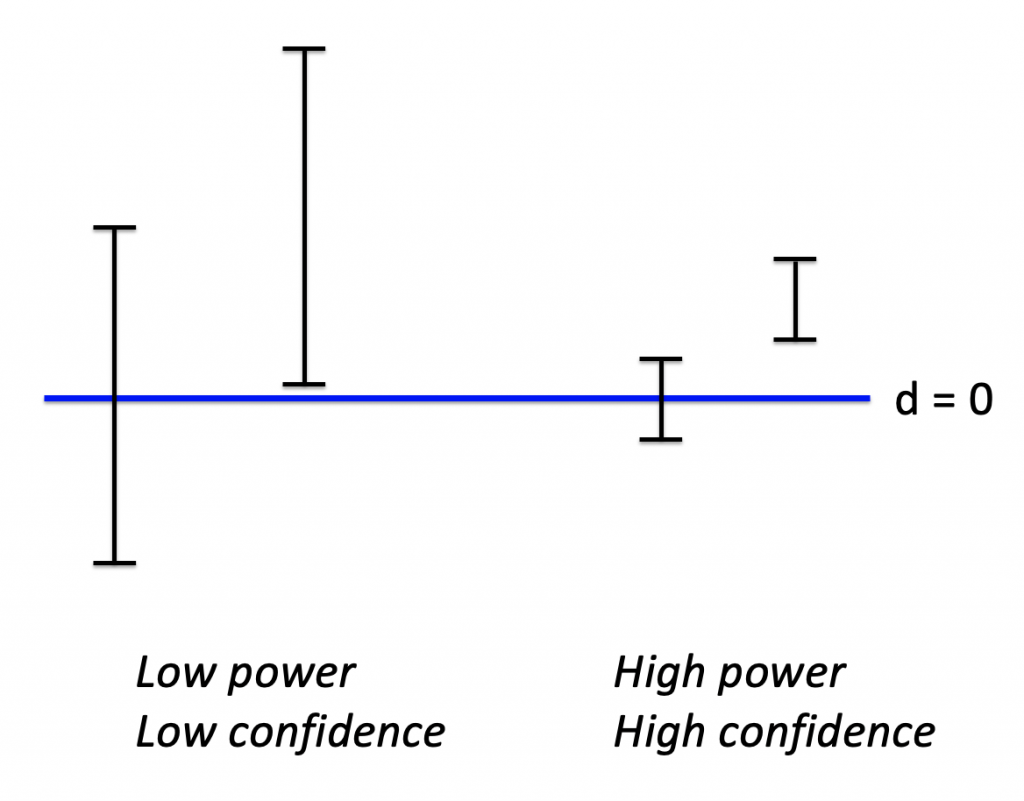

We could not fail to notice that in spite of the many variations of inattentional blindness experiments performed in the past 3 decades, no one had tried to measure the impact of fast motion on inattentional blindness, not even those who had created experimental setups that made the parametric variation of speed straightforward. In fact, the only studies that – to our knowledge – varied speed systematically at all tried slow and slower speed conditions (relative to background motion), concluding that duration on screen – not speed – matters for the detectability of unexpected objects. Thus, to our knowledge, the attention system had never been explored under conditions of fast motion, a very plausible and – in evolutionary terms – important stimulus.

So we did. Briefly, we used a high powered sample of research participants in 3 studies that included conditions where the unexpected moving object (UMO) was fast, relative to background motion. The first experiment was a replication of the original “Gorilla” study. The second experiment involved detecting an unexpected moving triangle when counting dots passing a vertical line and the third experiment replicated this, while also including conditions that featured triangles that were moving slower than the dots.

The results from these experiments are clear and consistent. Faster moving unexpected objects are significantly more likely to be noticed, implying diminished inattentional blindness. Importantly, this effect is asymmetric. Even though the UMOs are on the screen much longer when moving slower than the dots, remarkably the faster moving UMOs are much more noticeable. This rules out that mere physical salience (the contrast between stimulus features) is driving this effect – if it was, slower moving UMOs should be as noticeable as fast ones. But this is not the case.

In other words, far from being a deficit that somehow diminishes cognition – in the same way cognitive biases have been suggested to do – “inattentional blindness” might be ironically named, as it highlights the elegance and sophistication of attentional deployment.

As we mentioned, an organism does not know ahead of time what will be the most relevant stimulus at any given time, under conditions of uncertainty. In the real world, uncertainty is unavoidable, so it has to be managed. Put differently, it would behoove an organism to hedge their attentional bets before going all in on one goal. Fast motion is a reasonable evolutionary bet to signify highly relevant stimuli – be they predator or prey – that an organism should be apprised of, whether they expected them or not. And it is precisely with fast motion that we get – to our knowledge for the first time – demonstrably strong attenuation of inattentional blindness.

Thus, rebalancing top-down goal-focused attention with relevant bottom up signals such as fast motion allows an organism to eat its proverbial cognitive cheesecake (by focusing attentional resources on what matters as defined by an important task) and “have it” too, by allowing for fast motion to override this focus, thus hedging for potential unexpected real life threats.

On a deeper level, big data management principles suggest that it is critical to filter large amounts of information up front. As perceptual systems are in this situation – having to handle high volumes of information, it is plausible that a key task is to reduce the information, ideally by filtering by relevance for the organism. In this view, “inattentional blindness” is simply one way in which this filtering by relevance manifests. So this view is incomplete, as it only captures the part of filtering by relevance that is due to top-down, goal-dependent relevance. Other ways in which stimuli might be relevant is due to expectations or inherently relevance, like fast motion.

So, when tested under the right conditions, people behave smarter than commonly believed.

verage disagreement of 1.25 stars, out of a rating scale from 0 to 4

verage disagreement of 1.25 stars, out of a rating scale from 0 to 4

#Yannygate highlights the underrated benefits of keeping foxes around

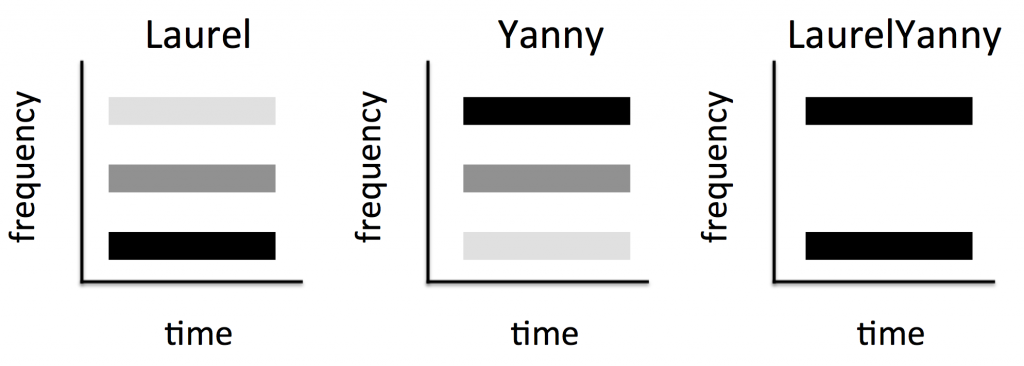

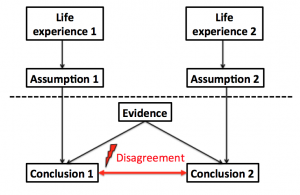

In May 2018, a phenomenon surfaced that lends itself of differential interpretation – some people hear “Laurel” whereas others hear “Yanny” when listening to the same clip. As far as I’m concerned, this is a direct audio analogue of #thedress phenomenon that surfaced in February 2015, but in the auditory domain. Illusions have been studied by scientists for well over a hundred years and philosophers have wondered about them for thousands of years. Yet, this kind of phenomenon is new and interesting, because it opens the issue of differential illusions – illusions that are not strictly bistable, like Rubin’s vase or the Duckrabbit, but that are perceived as a function of the prior experience of an organism. As such, they are very important because it has long been hypothesized that priors (in the form of expectations) play a key role in cognition, and now we have a new tool to study their impact on cognitive computations.

What worries me is that this analogy and the associated implications were lost on a lot of people. Linguists and speech scientists were quick to analyze the spectral (as in ghosts) properties of this signal – and they were quite right with their analysis – but also seemed to miss the bigger picture, as far as I’m concerned, namely the directly analogy to the #dress situation mentioned above and the deeper implication of existence of differential illusions. The reason for that is – I think – that Isaiah Berlin was right when he stated:

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

The point of this classification is that there are two cognitive styles by which different people approach a problem: Some focus on one issue in depth, others connect the dots between many different issues.

What he didn’t say is that there is a vast numerical discrepancy between these cognitive styles, at least in academia. Put bluntly, hedgehogs thrive in the current academic climate whereas foxes have been brought to the very brink of extinction.

Isiah Berlin was right about the two types of people. But he was wrong about the relative quantities. It is not a one-to-one ratio. So it shouldn’t be ‘the hedgehog and the fox’, it should be ‘the fox and the hedgehogs’, at least by now…

It is easy to see why. Most scientists start out by studying one type of problem. In the brain – owed to the fact that neuroscience is methods driven and it is really hard to master any given method (you basically have to be MacGyver to get *any* usable data whatsoever) – this usually manifests as studying one modality such as ‘vision’, ‘hearing’ or ‘smell’ or one cognitive function such as ‘memory’ or ‘motor control’. Once one starts like that, it is easy to see how one could get locked in: Science is a social endeavor, and it is much easier to stick with one’s tribe, in particular when one already knows everyone in a particular field, but no one in any other field. Apart from the social benefits, this has clear advantages for one’s career. If I am looking for a collaborator, and I know who is who in a given field, I can avoid the flakes and those who are too mean to make it worthwhile to collaborate and seek out those who are decent and good people. It is not always obvious from the published record what differentiates them, but it makes a difference in practice, so knowing one’s colleagues socially comes with lots of clear blessings. In addition, literatures tend to cite each other, silo-style, so once one starts reading the literature of a given field, it is very hard to break out and do this for another field: People tend to use jargon that one picks up over time, but that is rarely explicitly spelled out anywhere. People have a lot of tacit knowledge (also picked up over time, usually in grad school) that they *don’t* put in papers, so reading alien literatures is often a strange and trying experience, especially when compared with the comforts of having a commanding grasp on a given literature where one already knows all of the relevant papers. Many other mechanisms are also geared towards further fostering hedgehogs: One of them is “peer-review”, which must be nice because it is de facto review by hedgehog, which can end quite badly for the fox. Just recently, a program officer told me that my grant application was not funded because the hedgehog panel of reviewers simply did not find it credible that one person could study so many seemingly disparate questions at once. Speaking of funding: Funding agencies are often structured along the lines of a particular problem, for instance in the US, there is no National Institute of Health – there are the National Institutes of Health, and that subtle plural “s” makes all the difference, because each institute funds projects that are compatible with their mission specifically. For instance, the NEI (the National Eye Institute) funds much of vision research with the underlying goal of curing blindness and eye diseases in general. But also quite specifically. And that’s fine, but what if the answer to that question relies on knowledge from associated, but separate fields (other than the eye or visual cortex). More on this later, but a brief analogy might suffice to illustrate the problem for now: Can you truly and fully understand a Romance language – say French – without having studied Latin? Even cognition itself seems to be biased in favor of hedgehogs: Most people can attend to only one thing at a time, and can associate an entity with only one thing. Scientists who are known for one thing seem to have the biggest legacy, whereas those with many – often somewhat smaller – disparate contributions seem to get forgotten at a faster rate. In terms of a lasting legacy, it is better to be known for one big thing, e.g. mere exposure, cognitive dissonance, obedience or the ill-conceived and ill-named Stanford Prison Experiment. This is why I think all of Google’s many notorious forrays to branch out into other fields have ultimately failed. People so strongly associate it with “search”, specifically that their – many – other ventures just never really catch on, at least not when competing with hedgehogs in those domains, who allocate 100% of their resources to that thing, e.g. FB (close online social connections – connecting with people you know offline, but online) eviscerated G+ in terms of social connections. Even struggling Twitter (loose online social connections – connecting with people online that you do not know offline) managed to pull ahead (albeit with an assist by Trump himself), and there was simply no cognitive space left for a 3rd, undifferentiated social network that is *already* strongly associated with search. LinkedIn is not a valid counterexample, as it isn’t as much a social network, as it formalized informal professional connections and put them online, so it is competing in a different space.

So the playing field is far from level. It is arguably tilted in the favor of hedgehogs, has been tilted by hedgehogs and is in danger of driving foxes to complete extinction. The hedgehog to fox ratio is already quite high in academia – what if foxes go extinct and the hedgehog singularity hits? The irony is that – if they were to recognize each others strengths – foxes and hedgehogs are a match made in heaven. It might even be ok for hedgehogs to outnumber foxes. A fox doesn’t really need another fox to figure stuff out. What the fox needs is solid information dug up by hedgehogs (who are admittedly able to go deeper), so foxes and hedgehogs are natural collaborators. As usual, cognitive diversity is extremely useful and it is important to get this mix right. Maybe foxes are inherently rare. In which case it is even more important to foster, encourage and nurture them. Instead, the anti-fox bias is further reinforced by hyper-specific professional societies that have hyper-focused annual meetings, e.g. VSS (the vision sciences society) puts on an annual meeting that is basically only attended by vision scientists. It’s like a family gathering, if you consider vision science your family. Focus is important and has many benefits – as anyone suffering from ADD will be (un)happy to attest, but this can be a bit tribal. It gets worse – as there are now so many hedgehogs and so few remaining foxes, most people just assume that everyone is a hedgehog. At NYU’s Department of Psychology (where I work), every faculty member is asked to state the research question they are interested in, on the faculty profile page (the implicit presumption is of course that everyone only has exactly 1, which is of course true for hedgehogs and works for them. But what is the fox supposed to say? Even colloquially, scientists often ask each other “So, what do you study”, implicitly expecting a one-word answer like “vision” or “memory”. Again, what is the fox supposed to say here? Arguably, this is the wrong question entirely, and not a very fox-friendly one at that). This scorn for the fox is not limited to academia; there are all kinds of sayings that are meant to denigrate the fox as a “Jack of all trades, master of none” (“Hansdampf in allen Gassen”, in German), it is common to call them “dilettantes” and it is of course clear that a fox will appear to lead a bizarre – startling and even disorienting – lifestyle, from the perspective of the hedgehog. And there *are* inherent dangers of spreading oneself too thin. There are plenty of people who dabble in all kinds of things, always talking a good game, but never actually getting anything done. But these people give just give real foxes a bad name. There *are* effective foxes, and once stuff like #Yannygate hits we need them to see the bigger picture. Who else would? Note that this is not in turn meant to denigrate hedgehogs. This is not an anti-hedgehog post. Some of my closest friends are hedgehogs, and some are even nice people (yes that last part is written in jest, come on, lighten up). No one questions the value of experts. We definitely need people with a lot of domain knowledge to go beyond the surface level on any phenomenon. But whereas no one questions the value of keeping hedgehogs around, I want to make a case for keeping foxes around, too – even valuing them.

What I’m calling for specifically, is to re-evaluate the implicit or explicit “foxes not welcome here” attitude that currently prevails in academia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this attitude is a particular problem when studying the brain. While lots of people talk a good game about “interdisciplinary research”, few people are actually doing it and even less are doing it well. The reason this is a particular problem when studying the brain is that complex cognitive phenomena might cut across discipline boundaries, but in ways that were unknown when the map of the fields was drawn. To make an analogy: Say you want to know where exactly a river originates – where its headwaters or source are. To find that out, you have to go wherever the river leads you. That might be hard enough, just like when Theodore Roosevelt did this with the River of Doubt, arguably all phenomena in the brain are a “river of doubt” in their own right, with lots of waterfalls and rapids and other challenges to progress. We don’t need artificial discipline or field boundaries to hinder us even further. We have to be able to go wherever the river leads us, even if that is outside of our comfort zone or outside of artificial discipline boundaries. If you really want to know where the headwaters of a river are, you simply *have to* go where the river leads you. If that is your primary goal, all other considerations are secondary. If we consider the suffering imposed by an incomplete understanding of the brain, reaching the primary objective is arguably quite important.

To mix metaphors just a bit (the point is worth making), we know from history that artificially imposed borders (without regard for the underlying terrain or culture) can cause serious problems long term problems, notably in Africa and the Middle East.

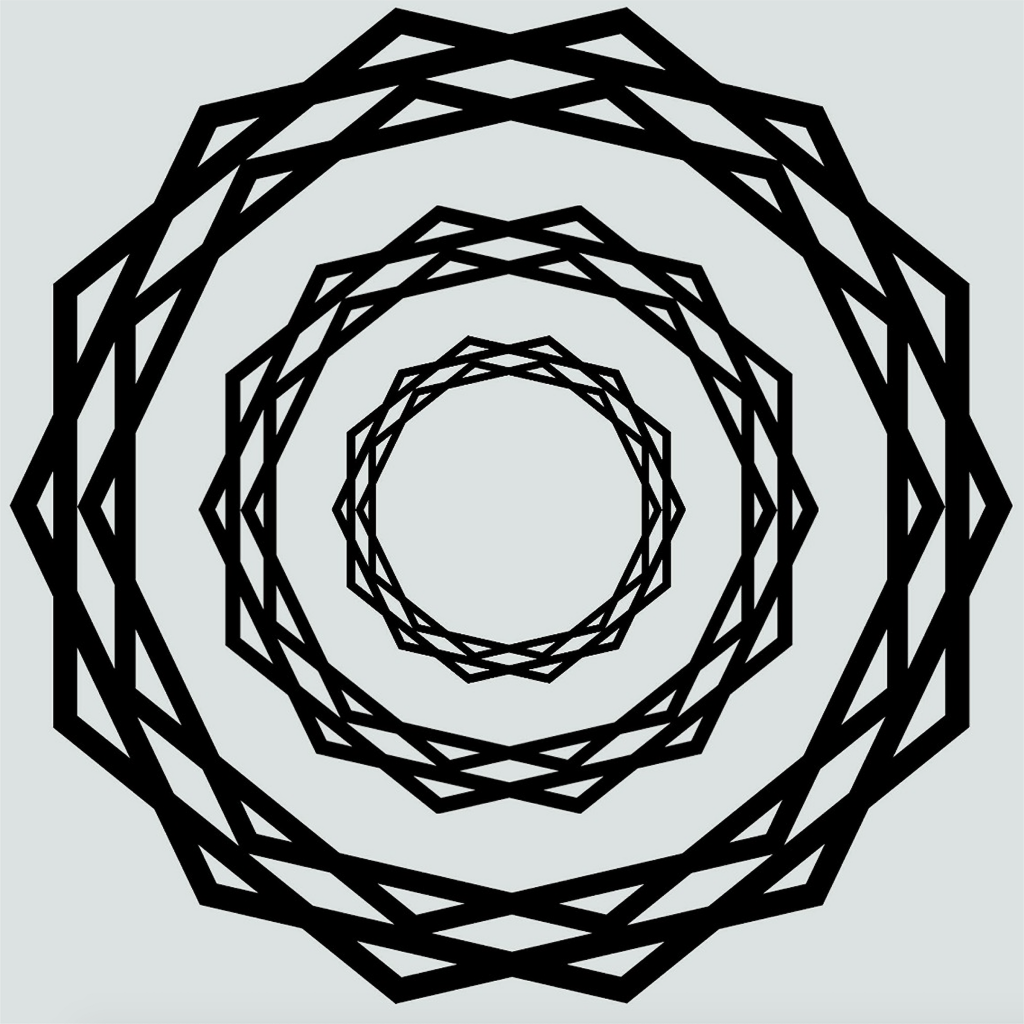

All of this boils down to an issue of premature tessellation:

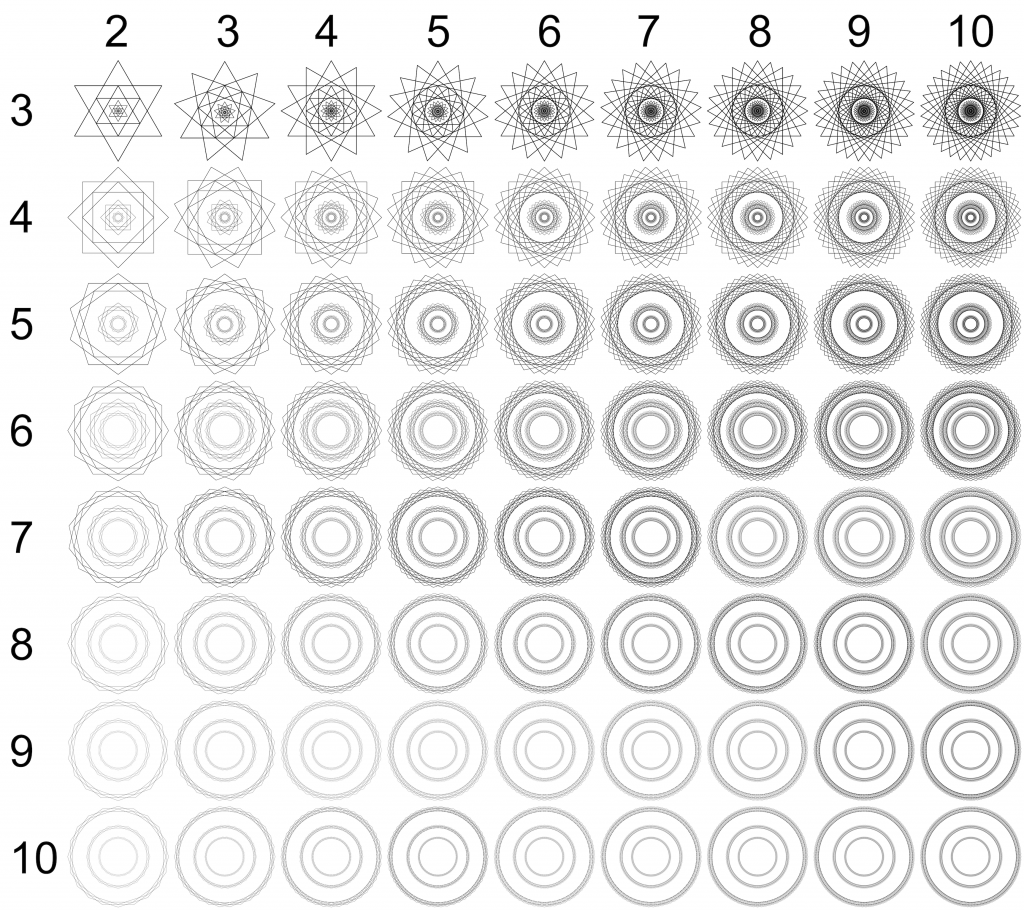

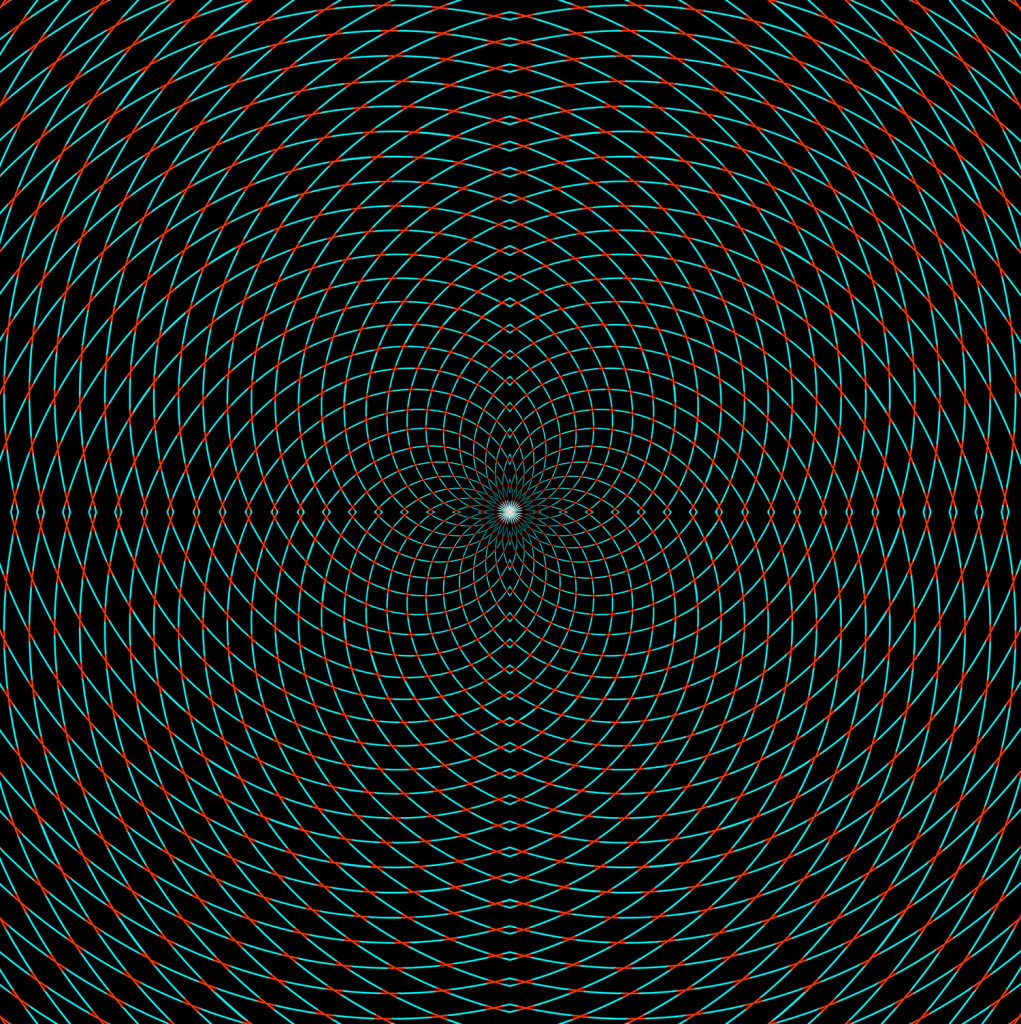

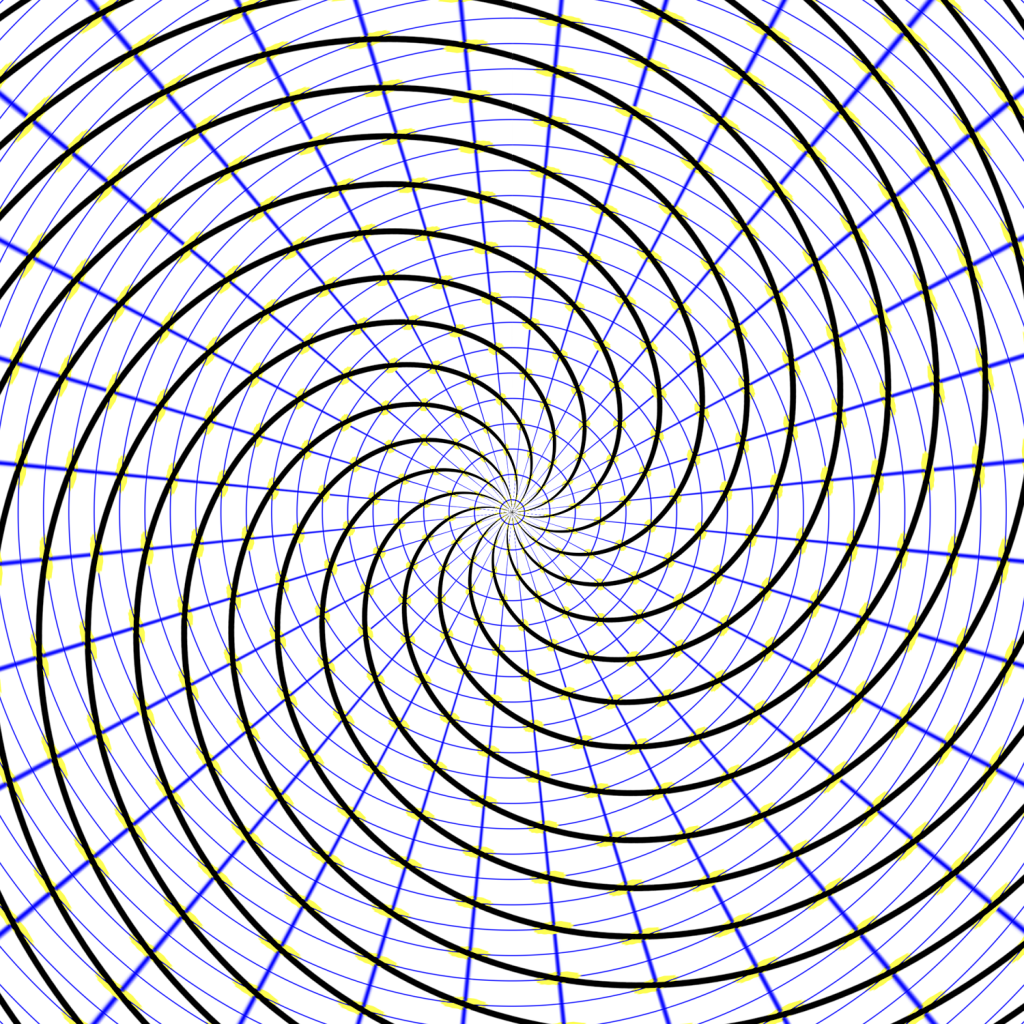

The tessellation problem. Blue: Field boundaries as they should be, to fully understand the phenomena in question. Red: Field boundaries, as they might be, given that they were drawn before understanding the phenomena. This is a catch 22. Note that this is a simplified 2D solution. Real phenomena are probably multidimensional and might even be changing. In addition, they are probably jagged and there are more of them. This is a stylized/simplified version. The point is that the lines have to be drawn beforehand. What are the chances that they will end up on the blue lines, randomly? Probably not high. That’s why foxes are needed – because they transcend individual fields, which allows for a fuller understanding of these phenomena.

What if the way you conceived of the problem or phenomenon is not the way in which the brain structures it, when doing computations to solve cognitive challenges? The chance of a proper a priori conceptualization is probably low, given how complicated the brain is. This has bothered me personally since 2001, and other people have noticed this as well.

This piece is getting way too long, so we will end these considerations here.

To summarize briefly, being a hedgehog is prized in academia. But is it wise?

Can we do better? What could we do to encourage foxes to thrive, too? Short of creating “fox grants” or “fox prizes” that explicitly recognize the foxy contributions that (only) foxes can make, I don’t know what can be done to make academia a more friendly habitat for the foxes among us. Should we have a fox appreciation day? If you can think of something, write it in the comments?

Action potential: Of course, I expect no applause for this piece from the many hedgehogs among us. But if this resonates with you and you strongly self-identify as a fox, you could consider joining us on FB.